by Ryan H. Flax, Esq.

(Former) Managing Director, Litigation Consulting

A2L Consulting

Research shows that visuals are a key to presenting information clearly and persuasively, be that presentation in a courtroom, an ITC hearing, the USPTO Trial and Appeal Board, a DOJ office, or in a pitch to a potential client. Because of what you can do with them and how your audience will psychologically react, if designed properly, trial timelines are one of the most important demonstrative aids you can use to be more persuasive.

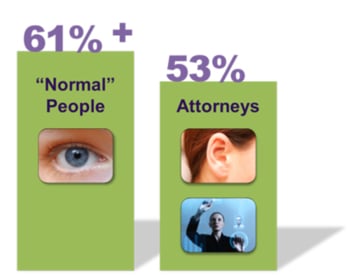

Studies show that the vast majority of the public (what I’ll call “normal” people – not us lawyers) learns visually – about 61% - which means that they prefer to learn by seeing. The majority of  attorneys, on the other hand, do not prefer to learn this way, but are auditory and kinesthetic learners – about 53% - which means we typically learn by hearing and/or experiencing something – we are different than most people. This makes sense, when you think about it – we all learned this way in law school by sitting through class lectures and we continue to learn this way as practicing attorneys by having to learn litigation by experiencing it. However, most people do most of their “learning” watching television or surfing the internet.

attorneys, on the other hand, do not prefer to learn this way, but are auditory and kinesthetic learners – about 53% - which means we typically learn by hearing and/or experiencing something – we are different than most people. This makes sense, when you think about it – we all learned this way in law school by sitting through class lectures and we continue to learn this way as practicing attorneys by having to learn litigation by experiencing it. However, most people do most of their “learning” watching television or surfing the internet.

No matter how smart you are, you typically teach the same way you prefer to learn, unless you carefully plan to do otherwise. Visual learners teach by illustrating. Auditory learners teach by explaining. Kinesthetic learners teach by performing. So, left to our own devices, we attorneys will usually teach by giving a lecture (consider your last opening statement, for example).

But, when you do this in an effort to persuade most “normal” people, you’re not playing the game to win. It is not sufficient to just relay information because that’s not how your typical audience wants to learn. You must bridge the gap between how you prefer to teach and how your audience prefers to learn, and demonstrative evidence, including graphics, models, boards, animations, and trial timelines are the way to bridge this gap, make your audience feel better prepared on the subject matter, feel it’s more important, pay more attention, comprehend better, and retain more information.

Besides simplifying the complex, providing an opportunity to strategically use familiar, well-understood pop culture templates, and satisfying your audience’s expectations of a multimedia presentation, trial timelines are a key component of your persuasion because they enable you to emulate generic fictions to produce a truth to be accepted by your audience. These are the four rules of thumb to effective visual information design.

Social psychology studies show that different sources of information are not neatly separated in juror’s minds. Trial timelines are one of the most effective ways to exploit this reality to be more persuasive at trial.

Visual meaning is malleable, so design your timelines to show a generic fiction you want the facts to fit: e.g., there was a reasonable cause for your client’s behavior or the opposing party’s actions directly led to the injuries we’re here about. The essential generic fiction for litigation (and all other circumstances, really) is that of cause and effect – people are intensely hungry for a cause and effect relationship to provide a basis, or perceived basis, in logic and reason for their emotional beliefs.

A trial timeline is the key visual aid for establishing a perception of causation relating to any set of facts. Once you induce such a perception of causation in jurors and they can adopt this perception as truth. This is the result you want in litigation. If you can set the factual stage for why your view of things makes more sense than your opposition’s version, you’ve won (unless the facts are devastating, in which case you should have settled).

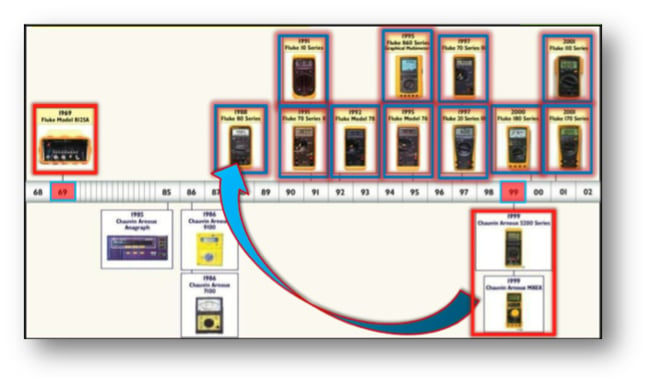

So, what perception of causation is being established by the first timeline (above) in this article? This timeline relates to a trade dress case where the design at issue was a yellow casing for an electrical device. What you’re seeing is how long our client used this yellow casing design (since 1969 and through the trial) at top, when the defendant changed its product to have a yellow casing (1999), and how similar their accused design is to our client’s product line.

You get all this information visually from a single trial timeline – it doesn’t just relay information, it tells a story. Imagine having the timeline at the top of this article on a large board and available to show the jury over and over again.

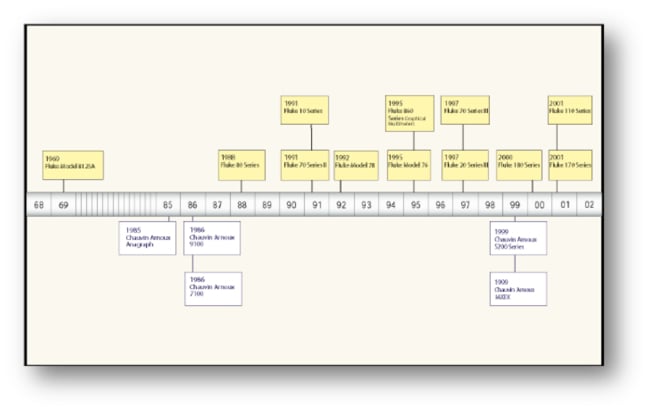

Here’s an alternative way of showing the very same information that is far less effective:

The same information is there, but there’s no self-evident story. There’s no cause and effect established. This is just no good as a persuasion tool, but this is what most attorneys think of when they consider developing a timeline (unless they envision the flags-on-a-stick conveying a series of events).

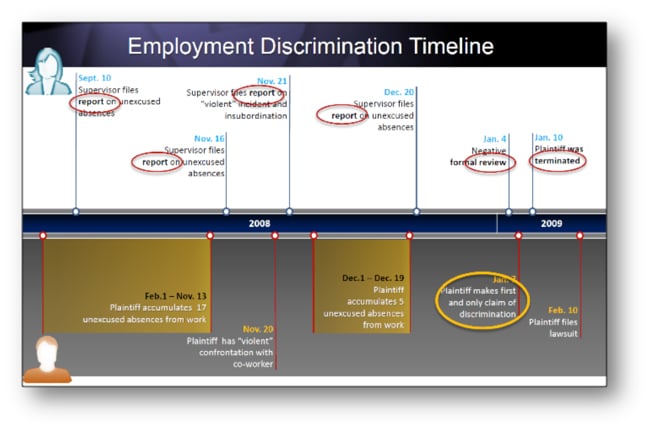

Here is a pretty standard, if attractive, trial timeline. It shows two series of related events. The series on top, as you might guess, relates to stuff our client did and the stuff in the shadows there on the bottom is what the opposing party did over the same period.

This rather simply, but clearly shows important interrelated events and very clearly establishes the key facts to induce the perception of cause and effect in the jurors. What do you learn from the timeline above? You learn that while the plaintiff claims that he was fired as retaliation for his claim of discrimination against his employer (and if you only knew that he made the claim and was then fired just days later you might believe him), the timeline shows that he had a terrible and well-documented history of unexcused absences from work and even a violent confrontation with a co-worker. This history is the real cause of the effect (his termination) and it’s all conveyed in this graphic.

You must feed a jury what it needs to find for you. The more a jury feels they understand where you’re coming from, the more you emulate generic fictions to establish a truth, and the better you induce the perception of cause and effect in your audience using the facts you know matter, the better your chances of winning.

Leave a Comment