“A jury consists of twelve persons chosen to decide who has the better lawyer.”

-Robert Frost

April Tate Tishler, Esq.

Regardless of who your client is, regardless of the facts underpinning your case, and regardless of whether you are happy with your chosen jury, the presentation of your case to the jury is of the utmost importance in advocating zealously for your client.

In recent years the “CSI effect” has invaded jury pools and resulted in entertainment-hungry jurors. While some attorneys may dismiss this effect as unimportant, as something to be overcome with perfectly sculpted rhetoric paired with just the right facial expression or gesture, it is a reality that all trial attorneys must consider.

Although the CSI Effect usually describes juror expectations and behaviors in criminal trials, the effect underscores a basic point that is also true of civil trials: juror’s expectations have changed in the last decade, in large part because of the evolving technology in both fact-based and entertainment-based media. Whether you as a trial attorney would share the same expectation if in a juror’s shoes is unimportant; what is important is that jurors today have much higher expectations regarding how trial counsel presents the theories and facts of a case.

Gone are the days when a trial attorney can simply pass around a paper copy of a key piece of evidence for the jurors to examine. Gone even are the days where counsel can get away with placing that same piece of evidence on an ELMO to project the document on screen. When juxtaposed with the savvy attorney’s use of dynamic presentations that incorporate clear and compelling graphics paired with 2-D and in some cases 3-D animation, these efforts seem outdated and pedestrian in most trials. The result, of course, is that the jurors judge the other side’s attorney as the “better lawyer,” who has at least attempted to satiate the jury’s hunger for a clear, palatable and persuasive presentation of the evidence.

Attorneys who insist on employing legalese and hyper-technical jargon buttressed by mundane and unimaginative exhibits can surely expect to lose. Not only does this result in a failure to inform the jury of the complicated facts and theories of the case, it results in a wholesale failure to motivate the jury to pay attention to your hard discovered facts and well-researched theories. For an attorney to blame the jury for his or her own failure to communicate a coherent case – perhaps complaining they have been provided with a particularly sensitive, undereducated, or simply unintelligent pool of candidates (1)– is naïve and ultimately unproductive.

Though you may not like it and though you may not know how to accomplish it, the effective use of demonstratives in jury trials is fast-becoming the only way to win a case. Indeed, a compelling graphic can mean the difference between a loss and a victory. Attorneys who embrace the jury’s heightened expectations of the visual presentation of their case and endeavor to quench the media thirst of its jurors will surely benefit from their leap of faith.

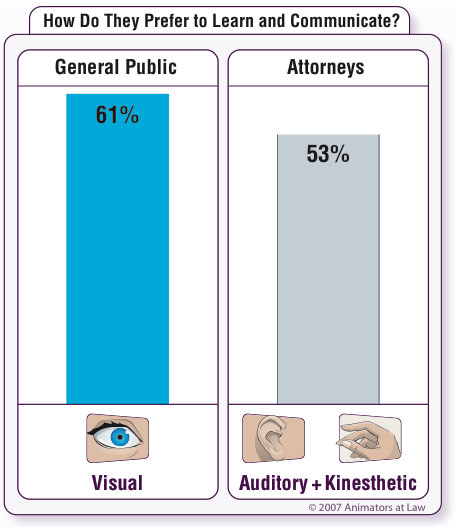

In 2003, Animators at Law (2) initiated and administered a study comparing the learning and communication styles of practicing attorneys and of the general public. Of the 2,044 individuals who took a thirty-question online survey designed to assess an individual’s preferred style of learning, 387 of the participants were practicing attorneys and 1,657 were not.

The three learning styles (3) assessed include auditory learners, kinesthetic learners, and visual learners.

Auditory Learners receive information best when they hear it. They prefer lectures, reading, wordplay and long conversations.

Auditory Learners receive information best when they hear it. They prefer lectures, reading, wordplay and long conversations.

Kinesthetic Learners learn best when they “experience” new information, often in the form of handling an object, learning a new hands-on skill or fully immersing themselves in a workshop-style learning environment.

Visual Learners learn best by watching. They enjoy television, and often utilize charts and whiteboards in a corporate setting.

Visual learners make up the vast majority of the population.

It is accepted that a person’s preferred means of communicating is almost always the same as one’s preferred means of learning. Repeated studies have found that the general population is approximately 65% visual, 20% auditory and 15% kinesthetic. (4) The Animators at Law study was inspired by this trend, and queries, simply, if the majority of the population is either visual or kinesthetic, why do attorneys who communicate with juries do so primarily by speaking to them?

Results of the Study

Results of the StudyThe differences in learning and communication styles between practicing attorneys and the general public are surprising. On average, a non-attorney is most likely to be a visual learner, and a practicing attorney is most likely to be a non-visual learner (i.e., auditory or kinesthetic).

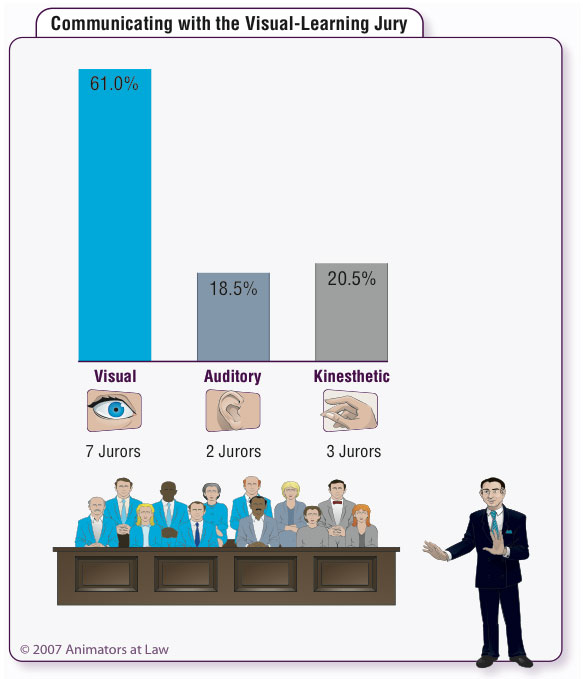

Since the general public is mainly visual, it follows that a jury – presumably representative of the general public – would also be mainly visual. Yet, the survey results reveal clearly that the majority of practicing attorneys are not visual. Since people will almost always communicate in the same style as they prefer for learning, and since the courtroom has long been dominated by oratory, it follows that a significant communication gap exists between practicing attorneys and jurors.

Based on the results of the study, a typical twelve-person jury would likely be composed of seven visual jurors, three kinesthetic jurors, and only two auditory jurors. Accordingly, if a litigator is not communicating by using visual and kinesthetic tools while presenting their case, they are under-communicating with 83% of the jurors.

In summary, attorneys and juries communicate and learn differently. Assuming that juries are a fair representation of the general public, one can reasonably conclude that juries and the attorneys who endeavor to communicate as effectively and efficiently as possible with them may, in fact, not be doing so.

Ultimately, we all want to be understood. As litigators, our clients are counting on us – and paying us – to be understood, and for us to represent their best interests in the most economic, efficient, and effective way possible. The use of visual evidence is key to accomplishing this goal.

An earlier study found that juror memory retention is increased by 650% when oral communication and visual information is combined. (6) Today’s trial attorney must therefore recognize and embrace the value of combining oral and visual evidence to demonstrate the facts and legal theories of the case.

How best, then, to combine oral and visual evidence? Edward Tufte, considered to be “the da Vinci of Data,” is an authority on this issue. Though not specifically referring to information displayed at trial, Tufte’s underlying theories are instructive in the courtroom context, and are the cornerstone philosophy of any capable demonstrative evidence provider.

Tufte argues that the presentation of data should never overwhelm the data itself. Graphical excellence consists of simplicity of design, and the complexity and truth of data. The goal is to communicate the data in a clear and uncluttered way. A classic example of his philosophy is the phone book: despite the fact that there are many thousands of pieces of data contained therein, the phone book is organized and displayed in a way that is clear, simple, and accessible without having to “unpack” or otherwise discern the data.

Tufte also warns against what he calls “chartjunk,” which is the display of non-informative or informationobscuring data that is merely decorative. One example of chartjunk is a legend that takes up half of the real estate on the chart itself. The solution to avoid this specific kind of chartjunk is to use direct labeling instead of a legend. Tufte similarly teaches about the “data-ink ratio,” arguing that the data is what is important, therefore ink should only be used to convey and display significant data.

Another important lesson to be learned from Tufte is that – contrary to most litigator’s tendencies – presenters should always assume that the audience is intelligent. Present the data in a clear and efficient way, and avoid “dumbing down” the data, and people will use their abilities to draw intelligent conclusions. One of Tufte’s most biting critiques is of the average presenter’s reliance on PowerPoint and other similar programs that he refers to as “slideware.” (7) In particular, he argues that the use of templates – and particularly bullet points – in PowerPoint weaken verbal and spatial reasoning, and almost always corrupt statistical analysis by omitting context and assumptions.

While Tufte’s assessment of PowerPoint is by and large correct, a wholesale dismissal of the program would be misguided in the context of litigation. PowerPoint is actually quite a useful tool for presenting graphics at trial: as a delivery mechanism, PowerPoint is flexible, non-threatening, and an accessible tool that lends itself very well to the trial environment. The key is to continually apply Tufte’s basic principles regarding the display of information when creating (or working with your demonstrative evidence provider to create) PowerPoint slides. Read: no bullets! Minimize text! Eliminate chartjunk! Increase the data-ink ratio! In the right hands, PowerPoint can be strong-armed into being a remarkably useful program, as long as Tufte’s caveats regarding the program are observed. In fact, the use of motion-pathing within the program allows a more creative and diligent graphic designer or animator to create some very sophisticated and useful 2-D animations. Remember, however, that PowerPoint will not create effective demonstratives for you: the key is to use PowerPoint, don’t let it use you.

As you may already believe, an effective demonstrative can win your case. A juror will know it when they see it, and will remember and remind their fellow jurors about it during deliberations. In fact, organizing your case into visual themes in the weeks and months before trial (and even in the earlier stages of motion practice) can be an effective tool to help you throughout the process of preparing for trial.

In addition to Tufte’s teachings regarding information design, there are several other guiding principles that are useful in the creation of litigation graphics:The most important aspect of effective demonstratives is the use of narrative in your presentation. In general, people are highly attuned to and interested in narratives, and court cases are no exception. Whether you are describing how an inventor came up with and patented an invention or describing how a complicated bank transaction is structured, the jurors will understand – and more importantly pay attention – when you tell a story with a beginning, middle and end. The use of tutorials to explain complicated concepts at the outset is an important jumping off point to set out the context for the case’s narrative. The use of compelling timelines and other demonstratives to display the chronology of the key events of your case will also advance that narrative. And your conclusion, as summarized in your closing statement and closing presentation, provides the jury with a bookend to your argument. Keep in mind that if you fail to provide your jurors with a compelling and coherent narrative, they often will make up one of their own that makes sense to them that may ultimately undermine the theory of your case. The narrative should be designed to offer the jury a clear path to your conclusion, so it will be impossible for the jury to imagine that it should be any other way.

Remember that your presentation should not be a way to organize your own thoughts or to reassure you as you speak – demonstratives are meant to underscore, explain, and compliment your rhetoric, not repeat it. You should say it, your demonstratives should show it. If you are reading the text off of your demonstratives, you have three big problems: 1) you are boring your audience, 2) you look unprepared, and 3) you’re wasting a prime opportunity to employ compelling graphics to further inform and persuade the jury.

When used properly, movement can also provide a dynamic element to your presentation while keeping the jurors’ attention. Whether building dates on a timeline one at a time, or incorporating simple 2-D animation to show each element of a process (such as the process of bankruptcy) or entity (such as the structure of a joint venture), or showing step-by-step the movement of a mechanical device, utilizing moving parts can be a very effective tool. Caveat, though, that movement for movement’s sake – or flashiness for flashiness’s sake – should be avoided at all cost. As in cooking, if an ingredient does not add to the integrity or point of view of the overall dish, it is best left out. If you think that blinking box in the middle of your presentation will draw the jurors’ attention, you are probably right. But if that blinking box is not doing anything, it is empty entertainment and is not enlightening or persuading your jury. If the jurors remember a blinking square, but they do not remember why it was blinking, you have created an ineffective, valueless (but most likely expensive) demonstrative.

Finally, it is important to understand and take advantage of the distinction between using demonstratives and using documentary evidence at trial. While most cases are document-intensive, it is unwise to overwhelm the jury with page after page of documents. If at all possible, whittle your paper evidence down to only the most important core set of materials. Even if you know there are fifty amazing quotes in thirty-five of your best documents supporting a material issue in your case, choose only the best one (or two) examples to show to your jury. Use the remaining juror attention span to illustrate the core themes of your case using compelling demonstratives. When you do need to call up key documents in the case, however, utilize a seasoned trial technician who is well-versed in the use of trial presentation software (such as Trial Director or Sanction) to call key documents up on the screen on command. These trial presentation programs allow the trial technician to zoom in, call-out, and highlight key portions of documents, to juxtapose two pages or two documents side-by-side for comparison purposes, to play back portions of deposition transcripts and deposition video, and to achieve many other similar effects. Trial technicians utilizing trial presentation software to project documentary evidence should be used in tandem with dynamic demonstratives to round out the juror’s knowledge of and interest in your case.

The following are a few techniques for creating compelling, understandable and persuasive demonstratives:

INFORMATIONAL GRAPHICS

In every case, there is a baseline of factual and quantitative information that must be presented to the jury, whether it takes the form of numbers supporting your damages calculations, dates and events that tell the narrative story of your case, or other objective data. With Tufte’s theories in mind, attempt to create graphics that communicate the information clearly and simply, while also attempting to further the themes of your case. While it may seem impossible to infuse these kinds of demonstratives with argument, you should always look for ways to underscore the objective facts with a touch of persuasion.

In the example below regarding the bankruptcy of an airline, the chart on the left simply quantifies the damages in a basic bar graph. In the alternative, the demonstrative on the right breathes life into the data while also adding a persuasive element: the debtor has carelessly wasted its money as if throwing it into a money pit.

VISUAL MESSAGING

Injecting visual messaging, however subliminal, into your demonstratives is  another effective way to persuade and inform the jury. This technique will also increase their retention not only of the underlying information but also the overarching legal point you are making.

another effective way to persuade and inform the jury. This technique will also increase their retention not only of the underlying information but also the overarching legal point you are making.

For example, in the case demonstrated below, the plaintiff sued the defendant claiming that the joint venture they formed together years prior was ruined by the unilateral decisions made by defendant affecting the joint venture. The evidence showed that even though the plaintiff claimed ignorance as to the dealings of the joint venture, plaintiff in fact sat on dozens of committees formed to oversee the joint venture.

Instead of simply listing the committees (as shown on the left), a more compelling way to portray this information is to use that same list and form it into the shape of an eye.

Counsel in this case used the demonstrative to bolster their oral argument that plaintiff clearly had its eye on the joint venture.

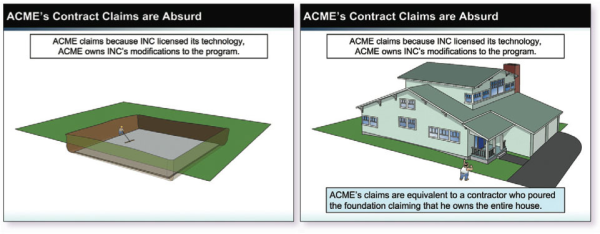

ANALOGIES

Even the most basic concepts can be better understood and retained when analogized with commonplace themes and ideas. The more complicated the concept, the more effective an analogy can be to efficiently explain the concept and to underscore the reasonableness of your theory (or the unreasonable nature of your opponent’s theory).

Even the most basic concepts can be better understood and retained when analogized with commonplace themes and ideas. The more complicated the concept, the more effective an analogy can be to efficiently explain the concept and to underscore the reasonableness of your theory (or the unreasonable nature of your opponent’s theory).

In the case below, the plaintiff claimed that it had intellectual property rights to the improvements and additions the defendant made to software it licensed from the plaintiff years prior. Not only is this concept legally unsound, when extrapolated into a real world example of the same theme, the plaintiff’s argument becomes absurd.

In the case below, the plaintiff claimed that it had intellectual property rights to the improvements and additions the defendant made to software it licensed from the plaintiff years prior. Not only is this concept legally unsound, when extrapolated into a real world example of the same theme, the plaintiff’s argument becomes absurd.

In another case, opposing counsel argued that a series of stock transactions that took place over the 14-month class period

adversely affected the overall price of the stock. To illustrate the absurdity of the argument, the demonstrative below utilizes dots and relative scale: the white dot represents the insubstantial number of post-IPO trades, while the remaining dots quantify the number of shares traded during that same period.

adversely affected the overall price of the stock. To illustrate the absurdity of the argument, the demonstrative below utilizes dots and relative scale: the white dot represents the insubstantial number of post-IPO trades, while the remaining dots quantify the number of shares traded during that same period.

Another compelling way to illustrate this same concept is to overlay a real world example  with relative scale. Here, the demonstrative illustrates the absurdity of the plaintiff’s argument by likening it to one runner in the New York marathon affecting all of the other 35,000 runners.

with relative scale. Here, the demonstrative illustrates the absurdity of the plaintiff’s argument by likening it to one runner in the New York marathon affecting all of the other 35,000 runners.

Offering your case as a narrative to the jurors is an effective way to keep them interested. As with any narrative, you must properly set the scene to provide context for the story. Regardless of whether you have to describe how a corporate financing agreement was structured, how a semiconductor device works, or what the law is in a particular area, a tutorial of some kind is key. The basic concepts in the case are hard enough to grasp for the average juror or even the judge who has no particular specialty in the area of law or technology about which you are litigating. Before you move onto the more esoteric legal theories, expert testimony and damages calculations, take the time and effort to explain to the jurors the basics. A 2-D animation can be particularly effective in this scenario, in that you can build the concepts and/or moving parts step-by-step while adding dynamic movement to your presentation. The key is to keep it simple and accessible to your jury.

As with the examples below, while it may be tempting to flash the inventor’s complicated schematics that were produced in  discovery as the basis for your description of a patented device at trial, a more useful utilization of the blueprint is to have your demonstrative evidence provider extrapolate out only the parts at issue, and re-illustrate them in a way that simplifies your explanation. As Tufte counsels, when showing parallels or distinctions, only the relevant differences should appear. Cut away any components that are not at issue in the case, and focus on the asserted portions to streamline your presentation. In this case, a simple isometric view of the asserted portions of the device was useful to explain the patented technology in a way that set the scene for a later discussion of the infringing device.

discovery as the basis for your description of a patented device at trial, a more useful utilization of the blueprint is to have your demonstrative evidence provider extrapolate out only the parts at issue, and re-illustrate them in a way that simplifies your explanation. As Tufte counsels, when showing parallels or distinctions, only the relevant differences should appear. Cut away any components that are not at issue in the case, and focus on the asserted portions to streamline your presentation. In this case, a simple isometric view of the asserted portions of the device was useful to explain the patented technology in a way that set the scene for a later discussion of the infringing device.

While I agree with Tufte that bullet points are deplorable in PowerPoint slides, they happen to be quite useful in static articles. To wit, the following are a few overarching tips and principles regarding demonstratives:

As a former litigator from a large, international law firm who then defected to a demonstrative evidence firm, I have a somewhat unique perspective on the industry. The findings of the Animators at Law study were certainly born out in my years at the firm: most attorneys with whom I had the pleasure of working were highly motivated, dedicated, and detail-oriented professionals, but they certainly were not visual learners or teachers. As one of the few visually-minded attorneys staffed on various trial teams, I was routinely tasked with working with the selected demonstrative evidence provider to create the graphics for trial.

In retrospect, my perspective on demonstrative evidence providers (or what I used to call “vendors”) is instructive. Most often, the choice of providers usually came down to all the wrong factors, such as familiarity (“I’ve got a guy I know who does graphics . . .”), price (“it’s the cheapest and my client wants to save money . . . “), and proximity (“these guys are right down the street . . .”). Now I know how perilous our decision-making process was, and better understand why the process of creating the graphics for trial was so arduous. And now I know that it does not have to be that way.

As the associate in charge of coordinating graphics for trial, I found myself spending countless hours managing the process of creating the demonstratives, endlessly grinding the square peg that was our graphics provider into the round hole that was our case and legal theories. Many billable hours were spent explaining and reexplaining the facts and core concepts of the case, and authoring pages of memos to attempt to clearly set out what I wanted the graphics provider to accomplish for us, only to sigh with disappointment upon viewing the delivered demonstrative which was often not what I asked for and frequently a day late. It became never-ending back-and-forth process of tweaking and changing the smallest typos and placement of graphics, all the while ignorant of the fact that if I had chosen the right vendor, I could have better spent my time prepping witnesses, writing trial outlines, drafting motions in limine, or even – gasp – getting some sleep in the days and hours before trial.

Now I know better. Now I am a demonstrative evidence provider, and I understand how to properly assist a trial team and help them win at trial. There are two kinds of demonstrative evidence providers: the good ones, and the bad. The latter often masquerade as the former, though there are some key indicators that will assist you in choosing the right provider.

Hiring the right graphics provider is like hiring an expert witness. The process can be a tricky business, though, because – similar to hiring an expert – it requires an abrogation of ego on the part of the litigator. It requires an admission that you are not a graphic designer, nor are you trained or experienced in effectively communicating data visually. Just as you would hire an electrical engineering expert witness to opine as to the interconnections of a patented device or an economics expert to render a report on the amount of financial harm your client has suffered, so too should you endeavor to find an expert in the field of information design to consult with you to create the most effective demonstratives for your case.

The following are the most important qualities to consider when vetting a graphic demonstrative provider:

Your time is valuable, and you and your team may have to work late at night or on the weekends to get the case ready for trial. So too should your demonstrative provider be available to assist you and your team in your time of need. Your provider should not only be available, they should be quick to respond and capable of turning around drafts quickly, no matter the day or hour. If the requested change will take more time that you may expect, your demonstrative provider should anticipate that expectation and should communicate the length of time the change will take and why.

If you are explaining basic legal concepts and/or ancillary procedural issues to your graphics provider, you have chosen the wrong graphics provider. They may not be as smart as you, but any good graphics team with relevant experience should understand the basics of your case even before you explain it. The very best consultants will have already pulled the docket for the case and familiarized their team with the factual and legal issues involved in the trial even prior to your first meeting. You should feel confident after your first consultation that your graphics team is resourceful, capable, and intelligent.

As mentioned above, just as when you hire an expert witness for trial, you should carefully select a graphics team that is expert in the field. Your graphics team should provide creativity and useful suggestions regarding how to best display the visual strategy of your case. While you may have an idea in your head about exactly how you would like to portray a certain theme or fact, you should trust your provider enough to give them an opportunity to suggest a better way of showing it. An effective team will create the demonstrative exactly as you envision it, and then create a few other versions of other ways to demonstrate the theme to provide you with some other options from which to choose.

Your graphics team should listen carefully to your expressed needs, and should assist you at the outset to properly determine the parameters of the project. They should tailor their services to your particular team and your unique case, and should be able to modify their services mid-stream to adapt to the changing needs of your team and the evolving issues in the case.

When seeking a graphics firm, you should not be looking for an order-taker – there is too much at stake and you will spend too many of the client’s resources on the graphics for the trial by working with a provider that is not adding real value to your team. You should look for a team that takes a proactive and consultative approach, and ultimately a team that provides you with impeccable service as well as unparalleled work product.

Your demonstrative provider should be open and honest with you at all times; honest not only about the costs associated with the service they will provide and their teams’ capabilities, but also honest with you about your case. Keep in mind that it is valuable to hear an outsider’s perspective on your case – ultimately, an outsider is more like a typical juror and less like you, since you have most likely been living with your case day in and day out for years before trial. Even though you know the most about your case, and have memorized every detail, an intelligent outsider who is expert at creating compelling graphics will be able to assist you in stepping back to take in the bigger picture. This broader perspective is ultimately all you will be able to effectively communicate at trial, so someone who has a better view of the forest for the trees is truly an asset.

Though the price of the demonstratives is certainly important to you and your client, be wary of selecting a vendor based largely (or solely) on price. Be mindful that some demonstrative evidence firms will low-ball the initial project bid to rope you in, only to add hidden costs and inefficient billable hours to your invoice with no regard to the original estimate. A conscientious demonstrative evidence provider will instead have a candid discussion with you regarding the cost of a project at the outset, and will endeavor to update you along the way as to where the billing stands against the original estimate.

That includes notifying you if the scope of the project changes in a way that increases the total expected cost of the project. While this change in scope may be due squarely to your own team’s expanding graphics needs as the trial approaches (or the trial schedule changes) and as the concepts and theories in the case inevitably evolve, a scrupulous demonstrative evidence provider will make sure to have a frank discussion with you regarding the change in scope and potential impact on the budget.

Always keep in mind that time equals money, whether it is your hours billed to your client or the demonstrative evidence firm’s hours. Be cognizant of how you and your colleagues (including support staff) are affecting the time and effort required of your demonstrative evidence provider and therefore affecting the invoice. While any diligent demonstrative evidence provider will happily work through the night to assist you in meeting a deadline, do not be surprised if you end up paying more for the around-the-clock service.

The best kind of demonstrative evidence provider will raise a red flag before the long night begins and notify you that your budget may be impacted by overtime hours if they haven’t already been built into the project estimate.

You should not have to “manage” your graphics firm – if they are failing to bolster your team and flow seamlessly with your process, they are not the right firm to get the job done. Your graphics provider should use tools that are workable for your firm and your trial team, and should not require their own proprietary software to create or display your graphics.

Ultimately, all of the factors above lead to the same issue: Trust. If you don’t trust your graphics provider,you shouldn’t hire them.

Endnotes

1. I submit that web writer Tim Cavanaugh’s description of the average American jury as “a bunch of louts, nincompoops, and media whores who need to stop trusting their guts and start listening to people smarter than themselves” is patently untrue and overwhelmingly elitist. See Tim Cavanaugh, Run Away, Jury! We’re Being Tried Before Dozens of Imbeciles, Reason Magazine, Nov. 2005, at http://www.reason.com/news/show/33148.html. While he might be right about the media part, that sentiment is certainly no way to win a case – the average American juror may not have a law degree, but they can smell condescension from a mile away and will certainly feel no compunction to find for your client if they find you patronizing and otherwise despicable.

2. Animators at Law is an attorney-owned and operated litigation consulting and trial demonstratives company comprised of creative attorneys and talented information designers. It was formed in 1995 and its core business is making complex information interesting and understandable to lay audiences using static trial exhibits, electronic presentations and all manner of animation. Animators at Law also provides in-court support personnel to facilitate the seamless presentation of graphics and other electronic evidence. From developing and implementing visual strategies to presenting evidence in court, the members of Animators at Law are experts in the realm of effective demonstratives.

3. Educational experts largely agree that people prefer learning new information in one of three primary ways: seeing, hearing or experiencing. See Maryann Kiely, Meta-Analysis of Experimental Research Based on the Dunn and Dunn Model, Journal of educational Research, 2005. See generally Rita Dunn, Kenneth Dunn, & G.E. Price, learning style inventory (Price Systems 1984).

4. See Bill Bradford, Reaching the Visual Learner: Teaching Properly Through Art, the law teacher (2004); Donovan R. Walling, teaching writing to visual, auditory, and Kinesthetic learners (Corwin Press 2006); Cheri Fuller, talKers, watchers and doeRs: unlocKing youR child’sunique learning style (Pinon Press 2004).

5. Other results from the study found that practicing attorneys are 10% more likely to be auditory learners and 4% more likely to be kinesthetic learners than the general public. Practicing attorneys are 14% less likely to be visual learners and communicators.

6. Harold Weiss & J.B. McGrath, Jr., technically speaKing: oRal coMMunication foR engineers, scientists and technical peRsonnel(McGraw-Hill 1963).

7. Edward R. Tufte, the cognitive style of powerpoint: pitching out corrupts within (Graphics Press 2003). See also Edward R. Tufte, PowerPoint is Evil: Power Corrupts. PowerPoint Corrupts Absolutely, wired Magazine, Sept. 2003, at http://www.wired.com/wired/archive/11.09/ppt2.html.

"We made the right decision when we hired you. You are absolutely the best."

Holland & Knight"I am very happy with the quality of A2L's work and happy with the graphics. One of the best jury consultants I have worked with."

Gibson Dunn & Crutcher"If you are in need of highly qualified, creative, diligent and personable providers of trial graphics, I recommend A2L. They were wonderfully helpful and supportive of our team and demonstrated, repeatedly, real skill in creating graphic and demonstrative exhibits that captured the essence of our presentation. Just as important, they did this under extreme time and quality pressure and, always, with a smile."

Foley & Lardner"Your team did a very nice job on the simulation in the engine case and I will certainly keep and your team in mind for future litigation support needs."

Finnegan"You guys were great, I’ll definitely use you again."

Fidelity National Law GroupPersuadius (formerly A2L Consulting) has extensive experience in complex litigation. For over twenty-five years, we have worked with all top law firms on more than 10,000 matters with at least $2 trillion cumulatively at stake. Persuadius (as A2L) is regularly voted best jury consultants, best trial consultants, and best litigation graphics consultants.

© Persuadius 1995-2026, All Rights Reserved.

Nationwide Contact: 1-800-847-9330