by Ryan H. Flax

(Former) Managing Director, Litigation Consulting

A2L Consulting

I believe we may be on the verge of a revolution in patent law. I spent 12 years practicing patent law, handling both patent litigation and non-litigation work (prosecution, opinions, licensing, counseling, etc.). I’ve spent the last few weeks paying close attention to, examining, and writing about the just concluded Apple, Inc. v. Samsung Electronics Co. Ltd. trial and the litigation graphics used by both sides – and it’s changed the way I think about U.S. patents and their value. There are two kinds of patents in the U.S.: utility patents and their step-brother, design patents. Guess who’s now taking its place at center stage?

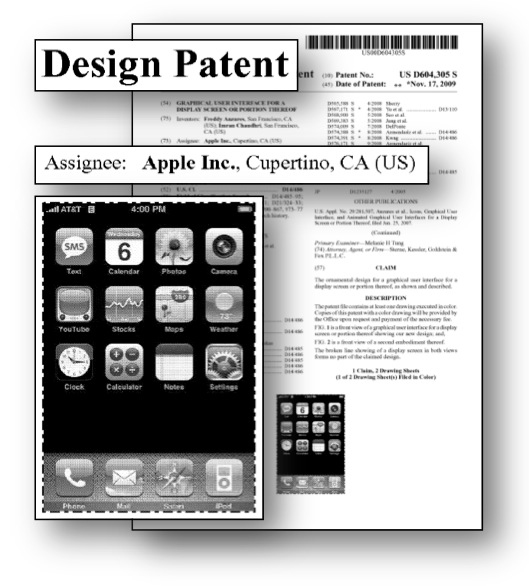

The Apple patents found infringed by Samsung were U.S. Utility Patent Numbers 7,469,381 (relating to the screen-bounce-back feature); 7,844,915 (relating to pinch-to-zoom); and 7,864,163 (relating to tap-to-zoom); and Design Patent Numbers D593,087 (design of iPhone back); D604,305 (iPhone home screen design, at right); and D618,677 (design of iPhone front). So, it was an even mix of design and utility patents. This strikes me as a possible turning point in the history of U.S. patents.

The Apple patents found infringed by Samsung were U.S. Utility Patent Numbers 7,469,381 (relating to the screen-bounce-back feature); 7,844,915 (relating to pinch-to-zoom); and 7,864,163 (relating to tap-to-zoom); and Design Patent Numbers D593,087 (design of iPhone back); D604,305 (iPhone home screen design, at right); and D618,677 (design of iPhone front). So, it was an even mix of design and utility patents. This strikes me as a possible turning point in the history of U.S. patents.

What really interests me are the three design patents enforced and found infringed (and valid) in this case. It is my sincere belief that if you polled patent attorneys in the United States, you’d find that 9 out of 10 feel (or, if they closely followed the Apple case – felt) that design patents were a bit of a joke. Sure, design patents have been around for years and have been successfully enforced here and there, but never at this scale of public importance, impact and damages awarded.

The jury awarded Apple about $1.05 billion, which could be as much as tripled by the Court because the jury found that Samsung’s infringement was willful. Now Apple is fighting for enhanced damages and a permanent ban on many of Samsung’s products. There is no way to discern exactly what the contribution of any one of the infringed patents is to this total damages award because the verdict sheet does not provide for this level of detail, but we do know that the three design patents contributed significantly and were each found not invalid. This presents the turning point I mentioned above.

When you consider the goal associated with acquiring patents – to derive value – and the means by which patent holders typically do so – by enforcing those patents in court, the value of design patents becomes clear. Design patents cover the way something looks and they are infringed when someone applies the patented design or a colorable imitation thereof without permission of the patent holder.

When you consider the goal associated with acquiring patents – to derive value – and the means by which patent holders typically do so – by enforcing those patents in court, the value of design patents becomes clear. Design patents cover the way something looks and they are infringed when someone applies the patented design or a colorable imitation thereof without permission of the patent holder.

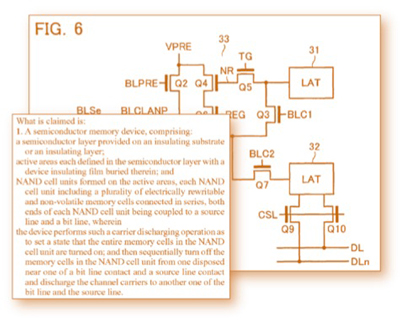

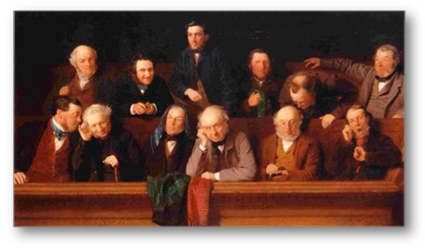

In court, you must convince a jury of this infringement, which means you must persuade the jurors that the accused infringer has copied your design. This is a far simpler task (e.g., “doesn’t this product look like this drawing?”) than teaching and persuading a jury that the flash memory circuit in the accused’s processor is the same as or equivalent to the “means for storing data” recited by the claim in your utility patent – get it? “Easy to explain” adds value. “Easy to build a story around” adds value.

In a process similar to a trademark or copyright case, juries are going to be called upon to look at a design (e.g., a laptop case, an automobile grill’s shape, a pair of yoga pants tapered leg) and decide whether it infringes a patent. If you think there’s a need for mock jury testing and litigation graphics in utility patent infringement cases, you can bet their essential in a design patent infringement case – they were in the Apple v. Samsung case. Your “story” of copying if you’re the patent holder or your “story” about independent design or the long history of similar design in the field if you’re the accused will have to be perfect to win.

In the Apple/Samsung case, a Samsung device called the Fascinate was found to infringe Apple’s ‘305 design patent. Here’s an image of the Fascinate’s screen display and icons alongside a color image figure from Apple’s design patent:

One of the images above is Apple’s intellectual property (well, maybe both are) and the other is a competitor’s product. What do you think? Can you tell which is which? Do you think the jury could?

Under the law as set forth by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit in Egyptian Goddess, Inc. v. Swisa, Inc., 543 F.3d 665 (Fed. Cir. 2008), the test for design patent infringement is “whether an ordinary observer, familiar with the prior art, would be deceived into thinking that the accused design was the same as the patented design.” This is a beautiful test if you’re a plaintiff’s attorney, particularly if you’re Apple’s attorneys. How much easier is it to simply hold up two pictures in the form of litigation graphics and ask, “Don’t these look the same?”

To win at trial, you have to get through to the people on the jury. They need to understand you and your case. In the typical patent case, this is no easy task, but when a design patent is at issue, the pictures can do much of the arguing for you.

To win at trial, you have to get through to the people on the jury. They need to understand you and your case. In the typical patent case, this is no easy task, but when a design patent is at issue, the pictures can do much of the arguing for you.

This underscores the importance of telling a convincing and persuasive story in court. Jurors want to reach the right result, so how do you help them do it?

Litigators must be effective at storytelling – jurors must be reached on an emotional level. To do this, litigators should take time to develop effective litigation graphics and test their story and theme with mock jurors in preparation for trial. With effective demonstrative evidence, also called litigation graphics, attorneys can teach and argue from their comfort-zone – by lecturing, but the carefully crafted litigation graphics will provide the jurors what they need to really understand what’s being argued and give them a chance to agree.

Most people (remember, jurors are people) are visual learners and do most of their “learning” by watching television or surfing the internet. In court, litigators must play on this battlefield and with the appropriate weapons. Design patents, in particular, lend themselves to this advanced style of litigating.

Another asset of the design patent is the type of damages available for infringement. Unlike damages for infringing a utility patent, the total profits relating to the infringing product can be awarded to the patent holder. That means, the entirety of infringement profits, rather than just the amount that could be reasonably attributed to the infringement, can be awarded. In the Apple v. Samsung case, this was a staggering amount; it won’t always be a billion dollars.

I expect to see a dramatic increase in the number of design patents filed-for and in the number of design patents litigated over the next year and beyond. Patent attorneys should rejoice in this new frontier!

Oh, and one more thing – in the images above, Apple’s patent drawing is the one on the left and Samsung’s product is on the right (or is it the other way?).

More resources related to intellectual property graphics and litigation graphics generally:

- Download the Patent Litigation Litigation Graphics E-Book

- Apple v. Samsung: Demonstrative Evidence & Storytelling

- Apple v. Samsung: Storytelling Proven Effective

- What patent litigator Ryan Flax found surprising after becoming a litigation consultant

- Information about patent tutorials for judges

- Information about Markman hearings

- 11 Tips for patent litigators using litigation graphics

- Explaining claim language

- Litigation graphics and ITC hearings

Leave a Comment