by Ryan H. Flax

by Ryan H. Flax

(Former) Managing Director, Litigation Consulting

A2L Consulting

I’ve written in several past articles (here and here) about what I saw as a true turning point for design patents in the United States. I explained that, based on the Apple v. Samsung trial in the Northern District of California, which provided a clear example of the presentation and litigation power of design patents as a sword against competitors, but also capped this off with the third-largest patent damages verdict in U.S. history regardless of patent type (utility or design), I believed that we would see more design patents being applied for and more design patents litigated. Well, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (Fed. Cir.) must really want me to be right.

Bed Bath & Beyond had won a ruling from the district court (S.D.N.Y) against plaintiff and inventor Roger J. Hall, sua sponte nonetheless, that Hall had failed to properly state a claim (in his complaint) for design patent infringement under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(b)(6). “[D]raw[ing] on its judicial experience and common sense,” the district court held that Hall’s patent infringement complaint didn’t contain “any allegations to show what aspects of the Tote Towel merit design patent protection, or how each Defendants has infringed the protected patent claim.” Rubbish – according to the Fed. Cir.

On January 25, the Fed. Cir. reinstated inventor Hall’s suit against Bed Bath & Beyond Inc. over his design patent, confirming that only a minimal threshold need be plead in a complaint to comply with the rules. The opinion confirms that in bringing a design patent case, the plaintiff need only comport with the standard notice requirements for pleading a complaint, rather than a point-by-point comparison of the patent and the accused design.

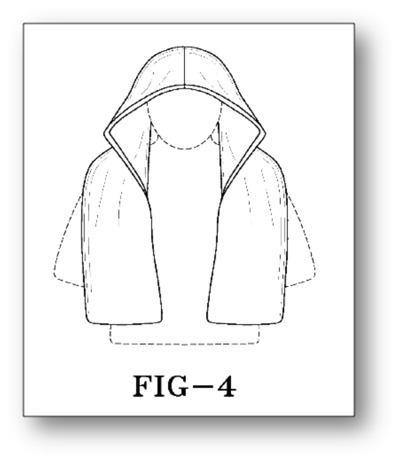

Mr. Hall’s patent is U.S. Design Patent D596,439, which is directed to a hooded towel. The design shows towel with a creased portion that can be worn as a hood (right). Hall calls the design a “tote towel.” In addition to confirming the low threshold for pleading a case of design patent infringement, the Fed. Cir. also confirmed the law of design patent infringement (as set forth in Egyptian Goddess, Inc. v. Swisa, Inc.) that infringement is based on the design as a whole rather than on discrete points of novelty.

Mr. Hall’s patent is U.S. Design Patent D596,439, which is directed to a hooded towel. The design shows towel with a creased portion that can be worn as a hood (right). Hall calls the design a “tote towel.” In addition to confirming the low threshold for pleading a case of design patent infringement, the Fed. Cir. also confirmed the law of design patent infringement (as set forth in Egyptian Goddess, Inc. v. Swisa, Inc.) that infringement is based on the design as a whole rather than on discrete points of novelty.

The criterion for infringement is “if, in the eye of the ordinary observer, giving such attention as a purchaser usually gives, two designs are substantially the same, if the resemblance is such as to deceive such an observer, inducing him to purchase one supposing it to be the other, the first one patented is infringed by the other.”

Said Mitchell Shelowitz (of Pearl Cohen Zedek Latzer LLP), Hall’s counsel, “[t]he ruling is the most important decision on design patent law since the Egyptian Goddess ruling,” and "clearly sets forth an unequivocal pleading standard for design patents that will be the leading precedent on this issue going forward.” (credit Law360.com for the quote).

Said Michael Powell (of Baker Donelson Bearman Caldwell & Berkowitz PC), “If you get sued, you want to know what you’re being sued for, and with a utility patent, that can be pretty complicated," he said. "When you have a design patent, the claim is one claim, which is what's shown in the drawing.” (credit Law360.com for the quote). Mr. Powell’s comment is compelling and falls in line with my belief that a design patent can be as valuable as a utility patent, but is easier to use at trial because of its simplicity. This makes a design patent, all other things being equal, more valuable than a utility patent because a good litigator can more easily explain it, more easily demonstrate its overlap with the accused design, and, thus, more easily persuade a jury of its infringement.

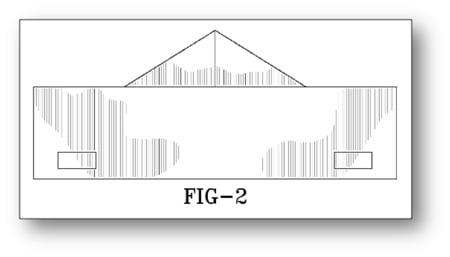

Here’s another drawing from Hall’s patent covering his design.

Here’s another drawing from Hall’s patent covering his design.

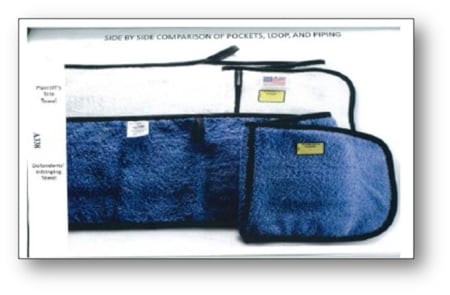

Consider again the criterion for infringement: if in the eyes of an ordinary observer, he/she may purchase the accused thing believing it to be the patented design – and take a look at the graphic Mr. Hall included in his complaint (below). Here is a picture of the accused towel (blue towel) and his design embodied in a reduction to practice (white towel).

How do you think a jury would react to such a graphic? How many words is this graphic worth in Hall’s complaint or in a subsequent summary judgment brief? This image truly shows the value of both design patents and their manner of proof – litigation graphics.

How do you think a jury would react to such a graphic? How many words is this graphic worth in Hall’s complaint or in a subsequent summary judgment brief? This image truly shows the value of both design patents and their manner of proof – litigation graphics.

A jury need only be convinced that these two things look pretty similar. Combine that with a decent story, e.g., “I pitched my idea to the defendant in confidence, disclosed all my secret designs, but they said they weren’t interested – I was stunned when I found out they’d come out with this new product just months later – and look how much it looks like my drawings.” This case simply reinforces my opinion that we’re on the brink of a design patent renaissance.

Other patent litigation and intellectual property litigation consulting resources on A2L Consulting's site:

Leave a Comment