Presenting securities cases to juries can involve difficult problems. Many jurors may have investments in the stock market or in mutual funds, directly or through their retirement plans, and may have some sense of how securities markets work. Some jurors, on the other hand, find all financial matters to be daunting. Furthermore, even fairly sophisticated jurors don’t have a good knowledge of accounting terms or of securities law concepts such as “causation” and “fraud,” which may have quite different shades of meaning in the law from their meanings in everyday life.

Thus, it is extremely important to present securities cases, which may involve issues of insider trading, fraud, or self-dealing, in ways that a jury can understand based on their basic knowledge of how a market works and their day-to-day sense of fairness.

In 2009, Kevin LaCroix, an attorney and insurance executive, wrote on his blog that covers issues of directors and officers liability, that in a particularly complicated securities case, an attorney referred in his opening statement to “EBIDTA; purchase accounting; debt service; noncash earnings; nonoperational accounting entries; free cash flow; liquidity; and dividends.” Another opening statement cited “negative cash flow; generally accepted accounting principles; and market capitalization,” and another referred to “options exercises; hedging and hedging transactions; and tax advantages.”

LaCroix concluded, “It is not that juries are incapable of figuring out these kinds of things. The problem is that these kinds of things put an enormous burden on the lawyers, the witnesses and the court to keep things clear; to avoid letting the trial get bogged down in technical minutiae; and making sure the jury is neither confused nor bored to death.”

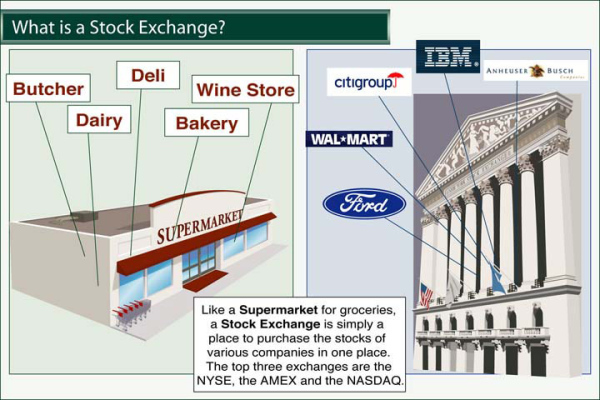

We have produced litigation graphics that are appropriate for jurors at all levels of knowledge. One basic and successful trial exhibit that we prepared simply asks, “What Is a Stock Exchange?” and responds that like a supermarket for groceries, a stock exchange is simply a central location to purchase the stocks of various companies. This is illustrated by a graphic of a supermarket and of the New York Stock Exchange, with examples of what is offered at each.

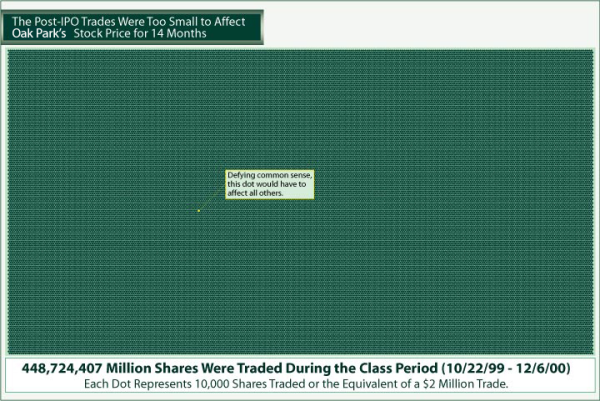

Originally printed as a large format trial board, another of our litigation graphics that answers a more sophisticated question is composed of 50,000 small dots, each representing the trade of 10,000 shares of stock. One tiny dot in the vast matrix represents the trades that were the subject of the lawsuit involving allegedly improper laddering transactions. The caption next to the dot reads, “Defying common sense, this dot would have to affect all others.” This caption appeals to jurors’ sense of logic, and the vast sea of dots is a memorable image.

In yet another case, we produced a set of line graphs in PowerPoint to show that over a period of time, a major investment bank was reducing its exposure to one country’s debt privately, while promoting the debt publicly. Again, a graphic illustration forms a clear depiction of a basic securities-law principle: One shouldn’t say one thing publicly while doing the opposite in private.

By appealing to a juror's common sense and using litigation graphics, a trial team can persuade even the most financially ignorant in securities litigation.

Leave a Comment