by Ryan Flax

(Former) Managing Director, Litigation Consulting

A2L Consulting

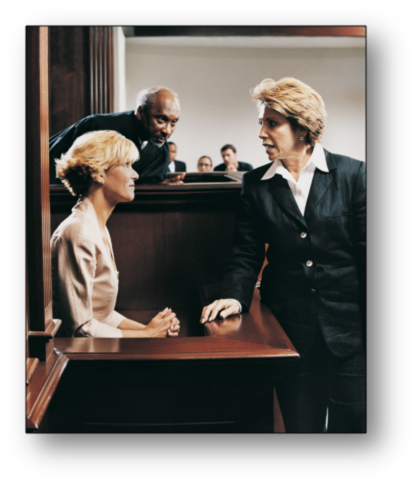

Litigators and their witnesses are confronted with difficult situations during testimony, and it’s nice to have reliable ways out of those sticky situations.

Expert witnesses are engaged to provide their expert insight and opinions supporting their client’s case during testimony and are there to tell the truth to the best of their knowledge when questioned at trial or deposition.

Litigators get paid to ask good and, at times, tough questions to get desired answers from the opposition’s witnesses and to help their own witnesses do their best.

During both courtroom testimony and in depositions there are common situations where an attorney tries to make things difficult for the witness. Below, I identify 14 of these common situations and provide some good strategies, both from my own experience as a litigator and from tips collected from attorneys and expert witnesses. Consider the points below when advising and preparing your witnesses for trial and depositions. The main and reoccurring principles are:

1. The “Yes or No” Question

If you’re a witness (an expert) you are going to be asked “yes or no” questions (where the forced response appears to be a “yes” or a “no”) on cross-examination or during a deposition. This type of questioning will put you in a tough spot because whatever you’re asked to respond “yes” to is most likely something you’d rather say “no” to, and vice versa. But, to be truthful, you’ll feel that you must answer in a way that seems counter to your beliefs or the foundations of your case.

There are many easy ways to get yourself out of this predicament. First, you need to identify that you’re in it. Then, in response to the question you say this: “I understand that you’re asking me for a ‘yes or no’ answer here, and I could answer you in that way, but doing so would be an incomplete answer and I don’t want to mislead you or the court.” Now, what have you done?

You’ve instantly made yourself look very reasonable in front of the jury/court and like someone interested in getting the “truth” out rather than an unreasonable (paid) witness who won’t answer questions. If the attorney asking the “yes or no” question insists that you go ahead and answer simply “yes or no” he looks like a jerk pushing his own agenda and uninterested in the truth – neither of which will help him in the jury’s or court’s eyes. It’s unlikely he’ll do this, but if he does, you go ahead and answer as he’s asked, but you’ve made him look bad and also have clearly identified the issue for re-direct from your own counsel.

2. The “Yes or No” Question – Take Two

As mentioned above, there are a variety of ways to get yourself out of the sticky “yes or no” question problem. So, in addition to the solution above, here are some additional tip/tricks to consider.

One expert witness has suggested that a response she uses to combat this situation is to go ahead and answer the question with the “yes” or “no” sought by the examining attorney, and then add, “under certain conditions,” with nothing further.

This presents the examining attorney with a dilemma. Should she let that answer stand? What circumstances is the expert referring to? Should she follow up and inquire about the circumstances the expert has in mind? Doing this surely exposes the attorney to a strong counter point by the expert. Responding in this way allows the expert to take the advantage.

3. The “Yes or No” Question – Take Three

Another expert surveyed for this article suggested replying to the “yes or no” question with, “as I understand your question the answer is [insert ‘yes’ or ‘no’].” As this expert explains it, this is a non-answer; it means nothing because there is no way for the lawyer to know how the expert understood his question and the answer can be either yes or no based on whatever is going on in the expert’s mind.

So, again, this begs the question: will the attorney follow up and allow the expert to express what’s on his/her mind? Again, advantage: expert witness.

As mentioned, experts will be asked “yes or no” questions during their deposition as they will at trial – the purpose being, once the examining attorney has probed the depths of the expert’s knowledge and bases for opinions, he or she will want to lock the expert into some position for trial. Just as in the trial testimony scenario, experts can use the same, and even more, techniques to wiggle out of this sticky situation during a deposition (I say “more” because you’re not responding in front of a judge and will have more flexibility).

There are other types of “sticky situations” expert witnesses will be confronted with during their examination by an attorney. Several are explored below.

4. “I Don’t Understand”

4. “I Don’t Understand”

As an expert witness, you’ll be subjected to some pretty tough, sometimes technical questions. Often the questioning attorney will offer a lot of hypothetical facts and complexity within a question. If confronted by such a question, when in doubt, respond that you just don’t understand the question and request that the attorney rephrase it.

At worst, this buys you a moment of time to consider the question. At best, you’ll throw off the questioning attorney, who may have carefully scripted his question because he or she simply had to in order to address the complexity necessary to the issue being investigated.

5. “I Don’t Understand” – Take Two

When you express lack of understanding and ask the attorney to rephrase a confusing question, sometimes the attorney will ask what was confusing to you. Don’t play this game. Don’t parse the question for what was clear and what was not.

The entire question was confusing and it’s his job to figure out a way to make it clear. Just make sure that, before you go this route, the question is at least too confusing for the jury to easily understand, otherwise, they’ll perceive you as playing games and being deceptive.

As mentioned, often, the examining attorney will have been asking his questions from a script that he or an associate prepared or that he obtained from a book. If the expert being examined is in a dense or very high tech field, the attorney may not understand the topic well enough to craftily rephrase his question.

6. “I Don’t Understand” – Take Three

Also, make opposing counsel define words if something could be ambiguous. Here’s an example based on the examination of a fact witness in a child custody battle:

Opposing counsel began asking leading questions to the mother in the case designed to try to paint her as a promiscuous parent who paraded men in front of her kids night and day. If you knew the mom, you would know how utterly laughable this tactic was. So, the examining attorney began the questioning by asking if the mom had “dated” anyone. The mom-witness responded to each of the attorney’s questions with her own, e.g., what do the terms “date,” “relationship,” “intimate,” “boyfriend,” etc., mean? The attorney finally gave up in frustration and the mom-witness's attorney got a good laugh out of it – the examining attorney got nowhere.

Don't assume you know what examining counsel means by the words he/she uses. Make them explain it (assuming doing so isn’t ridiculous enough to make you look stupid or difficult in front of the jury).

7. Think Before You Answer

The next common technique of examining-counsel is the use of rapid fire questioning. This is an easy technique to defuse since the witness can control the rate of questioning by taking the time to consider each question before answering. When the expert witness takes his time to answer, he also gives his counsel time to object.

Our CEO, Ken Lopez, was once questioned about an animation in a plane crash case and the question was something like: “the clouds in this animation are really like a video game aren’t they?” Ken explained, “I felt defensive, but choose to take my time answering. After a long pause, I replied, ‘I can't think of a video game like that works like that.’” He was surprised that the examining-attorney dropped the questioning at that point.

Remember, whatever you say is going permanently on the record – so make it accurate, make it useful, and make it count.

8. Don’t “Help” Them

8. Don’t “Help” Them

Most expert witnesses are, on some level, teachers. They want to instruct, inform, and educate. Often, the greatest and most sought-after experts are well-regarded university professors. This presents a problem when they’re under questioning at trial or (especially) in depositions. It’s often difficult for these witnesses to refrain from offering additional information, filling-in the pauses with education, and generally responding to questions that weren’t asked.

If an expert finds that their questioning attorney is at a loss for words, don't offer any. Let the uncomfortable silences sit there. Not an easy thing to do, but necessary.

If an examining-attorney asks a question that doesn’t get the science right, or misses the point somehow, don’t educate them. Let them stay ignorant and let the record stay ignorant until the right time to inform it, which is when the witness is on direct.

9. Don’t Guess

Remember, the expert’s testimony is forever on the record and will be held against him and his client if possible. If you can't answer a question, or don't know the answer to a question, say so. If your answer is an estimate or only an approximation, say so. If you think you might have the answer in the future, say, “I don't recall at this time.” If you do not remember, say so.

Never think that you must have 100% total recall or something even close. Do what you can before a deposition to refresh your recollection if it’s appropriate, but don’t refresh yourself on irrelevant or unhelpful things.

10. Don’t Guess – Take Two (or Stick to What You’re There For)

Another expert recognized that a standard trick is to get an expert to answer a question that is outside her experience because of the natural tendency to try and help by giving an answer. But, doing so can trap the expert because it then calls into question everything she has previously written and all her opinions expressed in court.

It is much better to simply say you cannot answer the question because it is outside your experience. So the cross examining counsel's armory is even further reduced. In addition, the image that the jury (or Judge) then has of you will further be improved. Knowing your business very well and the specific limits of your experience and expertise should garner your more respect.

11. Don’t Guess – Take Three (or Stick to What You’re There For – Take Two)

Following the previous note, what if the line of questioning moves to a subject for which your expert IS knowledgeable, but not there to talk about? He can’t say he doesn’t know how to respond.

Another expert suggests that if the subject matter of cross exam is not outside the expert’s experience, but is outside the scope work conducted in the matter, consider answering, at least in the U.S. – “I am sorry, but that work was outside of the scope of my retention in this matter, and so was not considered.” This expert gives the following example: “I have a specialty of deciphering Traffic Signal Timing plans to try and determine who REALLY had the green, as opposed who THOUGHT they had the green. In many of these cases, a separate Accident Reconstructionist is hired [as another expert]. If an Accident Reconstruction question is asked, it will most probably be within the scope of my EXPERIENCE and TRAINING, but is outside of the scope of my RETENTION in that matter.”

The danger of this scenario is that opposing counsel will try to drive a wedge between your multiple experts’ testimony, make them contradict one another, and diminish one or more of your experts and, thereby, your case. To combat this possibility, have your experts well prepared on what they are there to testify about. Have them stick to their expert reports, if they were required. Have them well prepared on what other experts on your team are testifying about and well prepared not to step on their teammate’s toes.

The danger of this scenario is that opposing counsel will try to drive a wedge between your multiple experts’ testimony, make them contradict one another, and diminish one or more of your experts and, thereby, your case. To combat this possibility, have your experts well prepared on what they are there to testify about. Have them stick to their expert reports, if they were required. Have them well prepared on what other experts on your team are testifying about and well prepared not to step on their teammate’s toes.

12. Only Answer One Question At A Time.

Compound questions are objectionable, whether in deposition or at trial. Nonetheless, have your experts prepared for this possibility. When asked multiple questions at one time, they should ask for clarification to be clear which part they are responding to. For example:

Q: Do you drink alcohol or take illegal drugs?

A: Yes to the alcohol; no to the illegal drugs.

There would often be an objection here. If there is no objection, and it is too complicated to easily respond to both parts, then do not be afraid to ask for the question to be restated.

13. Don't Let Yourself Get Cut Off

13. Don't Let Yourself Get Cut Off

Another expert recommends: “If there is more that you need to say, then say it. If that means adding it to the next answer or simply saying, ‘I'm sorry counselor, I wasn't finished answering your question,’ and then continuing,” then do it.

Also, be careful if asked a question that attempts to cut off your response, such as: “Is that everything?” Leave the door open in case you might have forgotten something. Respond to such a question with, “that’s what I can recall at this time” or something to that effect. Your attorney can try to fix any problems or misrepresentations on your redirect and it will be easier for the attorney to remind you what you have forgotten if you do not testify under oath that you have already covered everything.

14. Make Your Own Hypotheticals

Cross examination involving hypotheticals is common for experts. Another surveyed expert suggested that, when asked a hypothetical question, they are also very seldom complete – engineered that way to be more helpful to the opposing side and damaging to yours. This expert suggests responding with “I am sorry, that is an incomplete hypothetical, which I cannot answer as phrased. Would you like me to fill in the missing pieces and then give you an answer?” How can the examining-attorney possibly refuse and still appear reasonable to the jury?

I hope you find these points useful in preparing your expert witnesses if you’re an attorney or useful in preparing yourself for cross examination if you’re an expert. If you or your expert witness needs support in to prepare to testify, A2L Consulting is a valuable resource and here to help.

This article was exceedingly difficult to finish because all my experts who provided input kept providing new and helpful tips and examples. If you want to follow such new and helpful tips, join and follow the comments at the LinkedIn Expert Witness Network group here: LINK. If you have your own useful tips to add, please do so below in a comment below.

Other resources on A2L Consulting's site you may find helpful related to witness preparation and jury/trial consulting:

- Contact A2L about witness prep services performed by industry-leading consultants

- Free Download: Storytelling for Litigators

- How jurors evaluate expert witnesses vs. how lawyers do

- Witness preparation best practices - don't stay in the shallows!

- A2L Consulting Voted #1 Jury Consulting Firm by Readers of LegalTimes

- Social Media & Jury Consulting - 10 Things You Should Know

- A2L Consulting's Trial Consulting & Jury Consulting Services

- 13 BIG Changes Coming in Jury Consulting and Jury Research

- 3 Ways to Handle a Presentation-Challenged Expert Witness

Leave a Comment