Most of the lawyers that our jury consultants work with go to trial about once a year - if that often. Some might find that surprising, but it’s quite true that even the best big-firm litigators in the world don’t go to trial that often. How could they become so good when they get jury face time so infrequently?

All of these litigators have a gift for connecting with jurors. Most will regularly conduct mock trials and solicit advice from our jury consultants. They heavily use litigation graphics and work with our courtroom trial technicians, who ensure that the lawyer has his or her mind on his connection with the jury, not on his or her connection with the Internet.

But, even among the very best, there are some who are the simply the best of the best, and their habits are quite different from most. They comfortably rely on image consultants. They use acting coaches. They videotape themselves doing run-throughs, review the tapes, refine and repeat. And, more important than anything else, they practice openly in front of a group of trusted advisers. In a nutshell, they spend most of their careers asking, How can I be better?

When I watch these great litigators at work, I notice that they are a great deal like the fictional depictions of lawyers in the movies. And I don't think it is an accident. They've worked with jury consultants and other consultants to slowly mold themselves into who they are now.

I've written before about how lawyers can learn a lot about trial presentation from the movies, how the litigation business is not all that unlike the movie business and how litigators can benefit from learning to tell better stories - just like the movies. So, this got me thinking.

Since juries expect litigators to be a lot like those in the movies, and since the best in the business are not all that dissimilar from lawyers in the movies, might the gap in performance between good litigators and great litigators be the degree to which they practice?

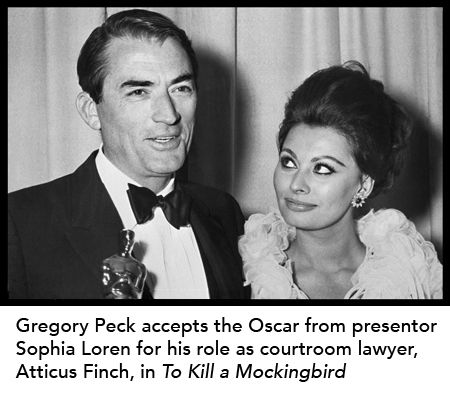

There is a noticeable gap between the way some litigators perform in the courtroom when compared to a Glenn Close, Paul Newman, Laura Linney, Matthew McConaughey or Gregory Peck. It's not just about their hair and makeup. It's about how they present their cases, how they connect better with jurors and how they tell better stories that are more emotionally compelling. So, rather than guess, I've turned to a few friends from the movie industry and asked them, How much practice goes into a performance like those we see in film?

Hollywood director John Carter has had a chance to work with and coach some of the best in the business. He observes, "Putting ego aside and working the material is critical to performance. A screenwriter spends months contemplating a character and a line of dialog before a final draft. Often the screenwriter listens to actors read the material long before production of a film. Then there is the rehearsal process involving props and wardrobe as the actor becomes the character, even masters the character. Imagine someone else playing Forest Gump. At one point there was just Tom Hanks and a script. That character came from a special collaboration and hard work. At some point, the great ones aren't even thinking about the material anymore, they have become the character. I wonder how much Roger Federer thinks about the mechanics of his serve before he hits it. Not much. After 17 Grand Slam titles, he still has a coach."

Hollywood director John Carter has had a chance to work with and coach some of the best in the business. He observes, "Putting ego aside and working the material is critical to performance. A screenwriter spends months contemplating a character and a line of dialog before a final draft. Often the screenwriter listens to actors read the material long before production of a film. Then there is the rehearsal process involving props and wardrobe as the actor becomes the character, even masters the character. Imagine someone else playing Forest Gump. At one point there was just Tom Hanks and a script. That character came from a special collaboration and hard work. At some point, the great ones aren't even thinking about the material anymore, they have become the character. I wonder how much Roger Federer thinks about the mechanics of his serve before he hits it. Not much. After 17 Grand Slam titles, he still has a coach."

Paul Dano, famous for his roles in films like Little Miss Sunshine and There Will Be Blood remarked, "It's hard to speak for anyone else, but I think a lot of actors enjoy their preparation. It is a time when you can learn, discover, and push yourself. I find the more deep my preparation, the more fun I have on the actual day of shooting. Each actor is very different, but I think hard work is the most common characteristic between the great ones I have worked with."

Paul Dano, famous for his roles in films like Little Miss Sunshine and There Will Be Blood remarked, "It's hard to speak for anyone else, but I think a lot of actors enjoy their preparation. It is a time when you can learn, discover, and push yourself. I find the more deep my preparation, the more fun I have on the actual day of shooting. Each actor is very different, but I think hard work is the most common characteristic between the great ones I have worked with."

Kaili Vernoff, who's appeared in multiple Woody Allen films, has also played a lawyer on TV in the series Law & Order. For her role, she noted, "by the time I'm on set, I've already run the scene with other actors - or my very supportive husband - until I know it back and forth. If I'm still stumbling over the words, I'm not able to breathe any life into the character. For professionals, it's that kind of practice and preparation that makes all the difference."

Kaili Vernoff, who's appeared in multiple Woody Allen films, has also played a lawyer on TV in the series Law & Order. For her role, she noted, "by the time I'm on set, I've already run the scene with other actors - or my very supportive husband - until I know it back and forth. If I'm still stumbling over the words, I'm not able to breathe any life into the character. For professionals, it's that kind of practice and preparation that makes all the difference."

Michael Allosso, has appeared alongside Steve Martin and others in a long career as actor and director for both film and stage. He said, echoing the teachings of our jury consultants, "Structure allows you to be more spontaneous. If you prepare, rehearse, practice - no matter how many flaws there are in those rehearsals - you will be ready to be more improvisational in the moment. Be impeccably prepared. Then, you are upping the chances of delivering a believable, natural performance."

Michael Allosso, has appeared alongside Steve Martin and others in a long career as actor and director for both film and stage. He said, echoing the teachings of our jury consultants, "Structure allows you to be more spontaneous. If you prepare, rehearse, practice - no matter how many flaws there are in those rehearsals - you will be ready to be more improvisational in the moment. Be impeccably prepared. Then, you are upping the chances of delivering a believable, natural performance."

Jules Haimovitz, former president of MGM Networks and former Vice Chairman and Managing Partner of Dick Clark Entertainment, sees a vast difference between prepared entertainers and those who extemporize. He reminds, "in the movie and television business, like in life, there is no substitute for careful preparation. Those who fly by the seat of their pants do not position themselves well for repeatable success."

Jules Haimovitz, former president of MGM Networks and former Vice Chairman and Managing Partner of Dick Clark Entertainment, sees a vast difference between prepared entertainers and those who extemporize. He reminds, "in the movie and television business, like in life, there is no substitute for careful preparation. Those who fly by the seat of their pants do not position themselves well for repeatable success."

So, just as our jury consultants suggested to me, it seems to me that litigators can learn a lot from actors, directors and movie moguls about preparation. As someone who also gives speeches and presentations regularly, I know that I am far better when I've prepared. No matter how many times I've done a run-through in my car or practiced in front of a mirror, there is simply no substitute for practicing in front of others. Yet, sometimes I, like many litigators, resist the humiliating feeling of not performing well, even in practice. But, I know, to get long-term gain, you often have to suffer some short-term pain.

That's where a great jury consultant or trial coach can come in. As my mentor reminds me from time to time, it requires two people to really grow yourself. This is true because the feedback you receive in real time is where much of your growth comes from. A jury consultant can provide feedback on everything from your style of dress, to how you use your hands, to how you structure your argument.

One key difference between a fictional lawyer and a real litigator is that some things just cannot be practiced. While you can practice your opening and closing until you're as convincing as Gregory Peck, learning how to conduct a good cross, managing objections, handling everything that leads up to trial as well as maintaining a good client relationship are all special challenges that no amount of memorization can prepare you for.

Ultimately, as some of Hollywood's brightest have shared and as our jury consultants remind, it is how you practice that defines how you present - and there are no short cuts.

Other resources from our jury consultants to help prepare more effectively:

- Evidence of careful preparation is a simple trial presentation

- Early trial preparation is critical - follow the 2 track strategy

- How to become a better storyteller for trial

- 16 Trial Presentation Tips You Can Learn from Hollywood

- Explaining the Value of Litigation Consulting to In-house Counsel

- 6 Reasons to Conduct a Mock Trial with Jury Consultants

- 10 Must-See Videos for Litigators from our Jury Consultants

Leave a Comment